Should we be paying more attention the structure of schools? A lot of facets of education are coming under scrutiny at the moment, both in the UK and abroad. The merits of various teaching styles, types of school, assessment formats and curricula among others are all being discussed. This debate is healthy and long may it continue. One facet, though, that very few seem to be questioning is the organisational structure of schools. Many, if not all, UK schools currently follow a hierarchical model. While this structure certainly can work, it is by no means the only possibility. Arguably, it is by no means the best.

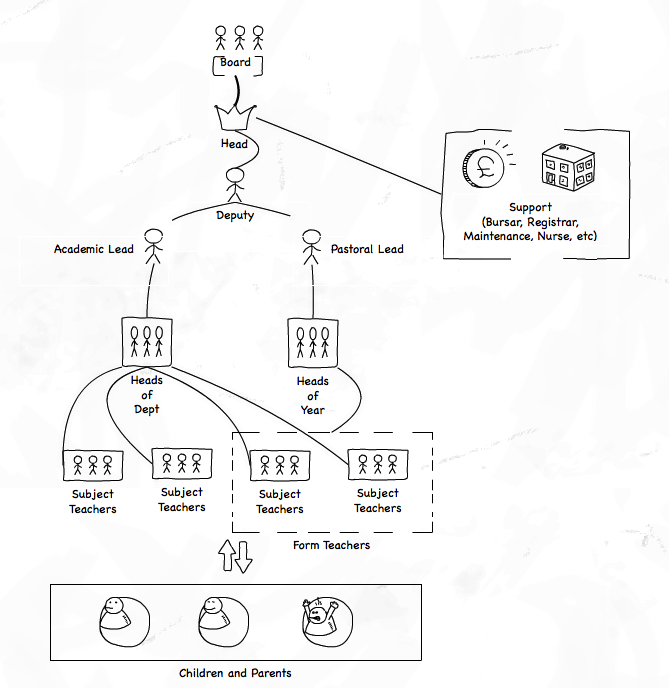

The current standard school structure, across state and private, sectors looks broadly like this

The focus of such structures is, at heart, the management of teachers and there are a number of advantages to such a structure, perhaps the most obvious ones being:

- specialisation,

- ease of co-ordination,

- control and

- security.

Benefits of Specialisation

Specialisation, both academic and in terms of role has some obvious rewards. In the classroom, at the most basic level, you have mathematicians teaching maths and musicians teaching music. Outside of the classroom, you avoid doubling up on tasks and again allow experts to come to the fore, whether it is organising school trips or technical infrastructures.

Easier Co-ordination

Related to this specialisation is ease of co-ordination. By giving everyone specific tasks it is far easier to reduce duplicated efforts, to streamline activities and to become more efficient at producing whatever it is you produce.

Control

Hierarchies also allow for tighter control and clear lines of responsibility. With things as precious as children, it is obviously paramount that we, as teachers, are in some way accountable for welfare, academic and otherwise.

Security

Lastly, hierarchies are, in schools at least, the devil we know. While this is not necessarily an advantage, it’s perhaps easy to underestimate the succour and security working within a familiar system can bring.

While hierarchies are a neat solution to structuring an educational organisation, their focus is on the management of teachers. As soon as we begin to shift that focus to the support of children and parents, this tidiness begins to fray. Hierarchies do not cope very well with complexity, variability or fluidity in their outside environment.

There are four disadvantages that are perhaps of particular importance for schools:

- not making the most of your staff,

- the Fordism of education,

- speed and agility and

- awareness and selective attention

Not making the most of your staff

The hierarchical model is perhaps most typically aligned with a military command-and-control approach or product-centred organisations such as manufacturers. In many ways it makes a lot of sense, especially given their life and death incentives, to learn from the army about how to command and control individuals within your organisation. Equally, given the obvious efficiencies of, say, a McDonalds or a BMW factory, one would think there is much schools could learn. There are two difficulties with this: first, that the approach makes it much easier to miss out on your staff’s potential; second, it runs the risk of a category mistake.

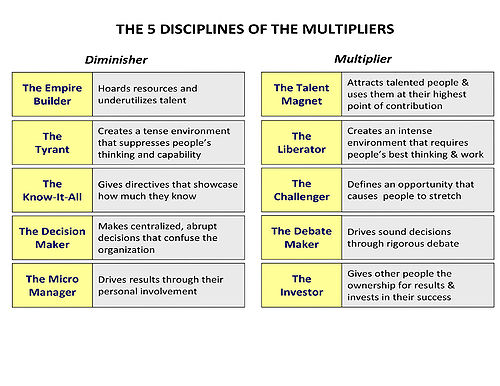

Liz Wiseman and her team studied 150 leaders in 35 different countries across four continents and found that leaders were either diminishers or multipliers. Diminishers got less than half of people’s intelligence and capability — about 48 percent. Multipliers, on the other hand, got twice as much (1.97 times) greater intelligence and capability out of their people

Now, hierarchies can have more than their share of multipliers. However, the command-and-control ethos underpinning a hierarchy makes them more prone to “diminishing” management and consequently preventing the staff from flourishing. Put another way, multipliers rely on a certain loss of control and hierarchies are designed to work against this.

The Fordism of Education

A second drawback with hierarchical structures in schools is what might be called the Fordism of education. The efficiencies that work so well in a McDonalds or a Ford factory do not necessarily translate to education or indeed any more complex task.

Ford’s famous factory at Highland Park was a paragon of hierarchical structures: dedicated equipment; semi-skilled workers (under a management regime based on Taylorist principles); a standardised product; and a move from craft to mass production (the assembly line). There were also technical innovations such as process engineering and standardisation with the inter-changeability of parts. Workers performed a simple task repetitively. There were also in a number of administrative and social control systems based on the Prussian bureaucratic model of the late-19th century: centralised materials requirements and logistical planning; control by rules; standard operating procedures; and the decomposition of tasks to their simplest.

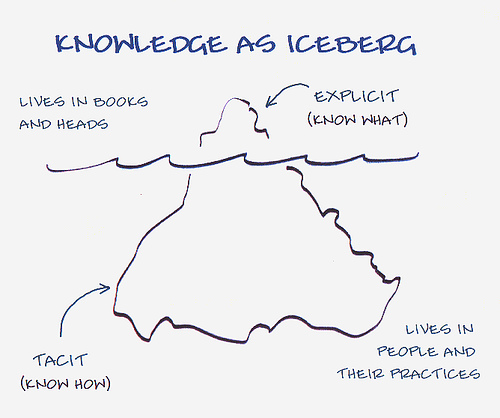

While the system works efficiently for products that are the same again and again (and indeed need to be), this sort of standardisation does not work for education, learning or knowledge. Polanyi made the distinction between explicit (that which can be codified and stored in media, such as a facts ) knowledge and tacit knowledge (that which cannot be codified and so is harder to transmit, such as how to write an essay).

Because of its focus on efficiency and management, Fordism over-simplifies education by focusing on the explicit, measurable knowledge (“to get an A you need to do X, Y and Z”) and by and large ignoring the tacit. Knowledge and learning become artificially tidy, transactional affairs rather than messy, socially negotiated activities. While every school and educational organisation has to deal with both types, because explicit knowledge is the easiest for these institutions to measure it is often these measurements that are used to see how well they are doing. Exams, test data and the like all provide explicit knowledge about the system and give cues as to how well (or poorly) the system is working. Again, while hierarchies do not necessarily encourage this limited “tip of the iceberg” view of learning, their support for learning is heavily biased towards a Fordist, transactional view of knowledge. There are two problems with this. First, by underplaying the tacit aspects of knowledge and learning, hierarchies make it easier to send the wrong message about learning to children. Second, the assessment of explicit knowledge is not sufficient in itself for any improvement plan.

Awareness and Selective Attention

The third disadvantage of specialisation is the lack of awareness it can bring. While specialisation has its benefits, it also has its risks. The clearest example of this is attentional blindness. If you have not seen it before, have a look at the following video and see if you can count how many passes the team in white make. Then see if you are right.

Selective attention is a fundamental problem. On a narrow level, we begin to focus so much on the fact that Miss Brodie is a French teacher that we miss out on the fact that she is a concert level pianist. On a broader level, the maths department might focus so closely on their assessment targets that they do not see the opportunities for collaboration or cross-fertilisation with the art or science that students are learning. On a broader level still, schools focus so intensely on OFTSED inspections that they miss out on the broader picture that in turn would help them reach “outstanding”.

Speed and Agility

Lastly, hierarchies are prone to being stick-in-the-muds. As anyone who has dealt with bureaucracies knows, the larger the hierarchy, the slower, and more frustrating, the response. Schools, similarly, often appear to be lumbering beasts that seem blind to many of the concerns of children and parents. Given the perceived importance these days of being able to keep up with the changes in the world around us, lumbering is not a good adjective to have earned. Broadly speaking, there would appear to be two factors in this image: locus of control and locus of importance.

Most of the time, this lumbering image is simply a matter of the locus of control. The speed of a decision or response is related to the number of rungs there are in the ladder there are between an outsider’s point of contact with the organisation and the where the decision gets made. In a typical school, following a variant of the structure above, there are four or five rungs between child (and parents) and head. There are, of course, ways to speed up this decision chain. Schools often try to involve the parents in what they do (though often this ends up being PR rather than actual engagement). Again, many parents try to short cut this chain by going straight to the top. This may get them a quick decision from the head but has the two obvious effects of slowing down the head and demotivating the initial point of contact “on the ground”.

Sometimes, sadly, the lumbering response is a matter of locus of importance. The language of hierarchies – top dog, pecking order and the like – implies that the further up the chain of command you are, the more important you are. Some management will always believe the hype, in which case the message becomes the lower down one is (whether frontline teacher, child or parent) the less importance one has to the school (and the less impact in decisions). Again this does not always happen. Teachers, almost by definition, will often put their students interest top.

Good management will often sidestep many of these issues by pushing power to the edge. In the corporate world, one example would be Nordstrom (the American retailer famed for its customer service). They avoid this lumbering by actively inverting the hierarchy, putting the customer at the top. As a result, the salespeople are expected to do everything in their power to keep the customer happy, and management’s role is to support the salespeople in that job.

Similarly the military are actively exploring ways for them to be effective when the theatre of war is messy and unpredictable. In cases where the situation is too complex or uncertain to give detailed orders, the military use a style of management called “Command intent”. This is a set of goals and a vision for possible methods of achieving those goals. It’s sufficiently high-level that it can be broadcast widely to everyone in the system, and front-line troops can then interpret how those goals apply to their front-line situation. The British army define it as:

“similar to purpose. A clear intent initiates a force’s purposeful activity. It represents what the commander wants to achieve and why; and binds the force together; it is the principal result of decision-making. It is normally expressed using effects, objectives and desired outcomes….The best intents are clear to subordinates with minimal amplifying detail.”

Power is pushed to the frontline.

The point is not that hierarchies do not or cannot work. They clearly can and do. The point is that hierarchies may not be the best structures for the job of education. By definition, they are slow to adapt and respond. Their design means they run the risk of belittling and/or alienating the children and families they are designed to serve, of not getting the best out of staff and of teaching children lessons we may not want them to learn. As Antoine De St Exupery put it, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”

A podular alternative

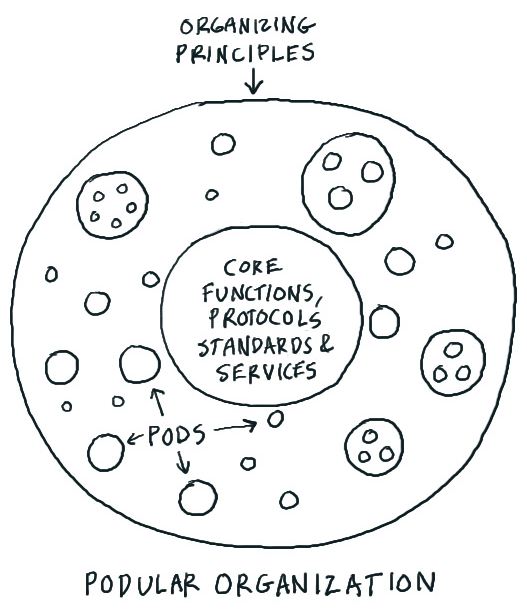

So how else could we structure schools and what would the advantages (and disadvantages) be? There are a number of options – I have yet to work my way through Mintzberg – but as an example, one alternative might be to mimic what Dave Gray has called “podular” organisations.

In his own words,

“One of the most difficult challenges companies face today is how to be more flexible and adaptive in a dynamic, volatile business environment. How do you build a company that can identify and capitalize on opportunities, navigate around risks and other challenges, and respond quickly to changes in the environment? How do you embed that kind of agility into the DNA of your company?

The answer is to distribute control in such a way that decisions can be made as quickly and as close to customers as possible. There is no way for people to respond and adapt quickly if they have to get permission before they can do anything.If you want an adaptive company, you will need to unleash the creative forces in your organization, so people have the freedom to deliver value to customers and respond to their needs more dynamically. One way to do this is by enabling small, autonomous units that can act and react quickly and easily, without fear of disrupting other business activities – pods.

A pod is a small, autonomous unit that is enabled and empowered to deliver the things that customers value.”

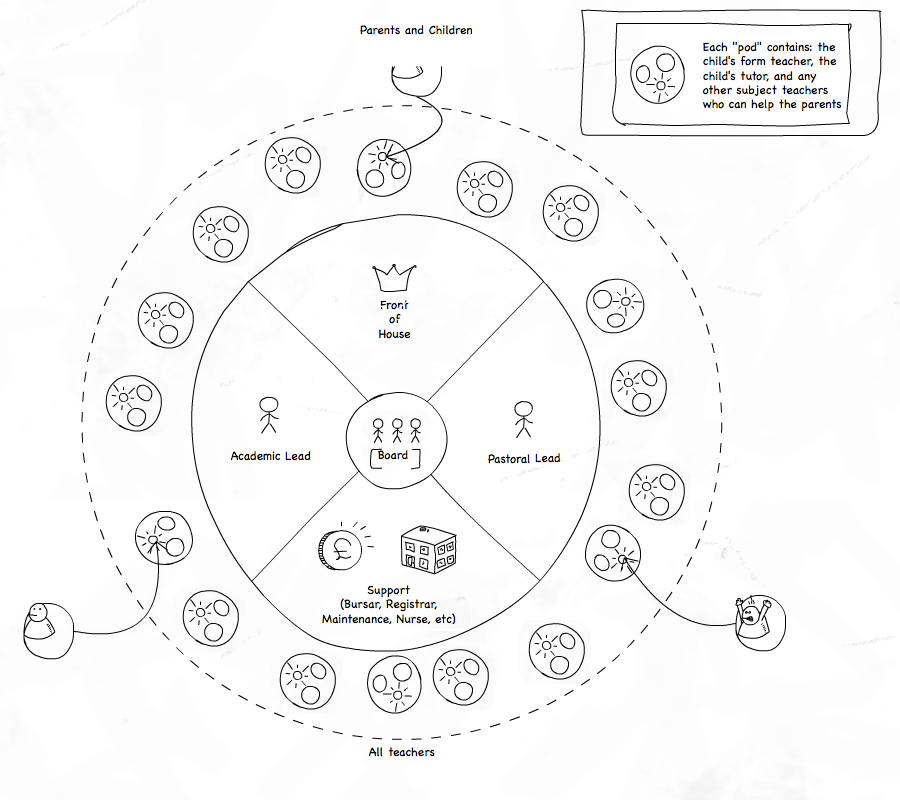

Podular Schools

One could apply a similar structure to schools without too much disruption.

How would this mitigate the four disadvantages of hierarchies?

Not making the most of your staff

Bad management is bad management. There is nothing to say that podular organisations will stop that. However, they do shift the balance. Because power is pushed to the edge and teh frontline decision makers, managers are starting from a point of a “multiplier” which is an advantage.

Fordism of education

In just the same way that hierarchies don’t necessarily mean a rich view of learning, poduar schools do not necessarily stop a view of education that is heavy on explicit knowledge and assessment. That said, the design is such that people working in a podular school, be they teachers or children, need to work hard to avoid a more collaborative, flexible open view of knowledge.

Awareness and selective attention

The fluidity of these systems puts an emphasis on people being able to contribute in anyway they can rather than in the way the organisation dictates. There can still be specialists in this sort of set-up, and there can still be departments. The difference, though, is that the department becomes a core service for form teachers, subject teachers and anyone else to use. As a result, there may well be less

Speed and Agility

By design, these organisations are more agile and quicker to respond than pure hierarchies. Even if the locus of control is the head, there are still only two “rungs” in the decision chain. Similarly, the locus of importance is by design the boundary between family and school. Parents and children have one constant person to turn to who will – and can – act as bridge between what the school can do for the child and the situation the child finds him/herself in.

Again, because power is pushed to the edge rather than kept at the top, those on the ground are given rein to use their best judgement to help the child or parent as quickly and as well as they can. This is not to say that teachers suddenly become shoot-from-the-hip lone rangers – they will still need to consult with colleagues and build consensus around whatever solutions they propose. But parents and children should get a far better, far more human service as a result.

Podular structures are just one possibility for structuring schools differently, and potentially more effectively. I’d love to hear people’s thoughts: other options, is this all a lot of nonsense etc.

@piersyoung like your thinkning on this – not least because it’s questioning the current status that has evolved rather than been planned.

[…] might, be a little more complicated than putting more computers in classrooms. I do wonder whether, at some level, the school as an organisation will have to undergo a similar redesign to make the most of our new […]