Part of leadership is correctly recognising the environment in which we are operating. To be able to do that, we need a) to understand what the different types of environment are, and b) understand what their distinctive qualities are. That gives us a theoretical appreciation, but it may also be useful to have an appreciation for what can happen when leaders don’t recognise the environment correctly, and an awareness of why we might all be prone to misdiagnosing.

3 Broad Views: Clockwork, Chaotic and Complex

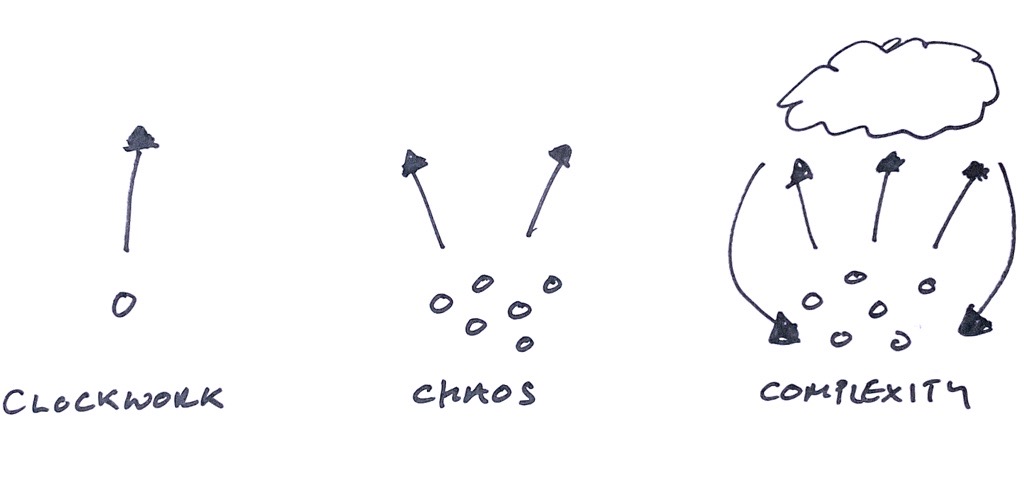

In his book Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, Roger Lewin summarises 3 basic views of a system: clockwork, chaotic and complex.

To repeat an old post about his summary, first we had a clockwork universe. It was a) linear, and b) static. That’s to say, from a set of known inputs, a result could be predicted. This is the world of Newton’s laws of motion and the like.

Then we had chaotic universe. It was a) non-linear, and b) dynamic. It was non-linear in that it wasn’t easily predicted. A classic example of this is the butterfly effect. It was dynamic in that the universe comprised lots of little interacting things. And there are lots of non-linear dynamic systems in nature: economies, embryos, and the like.

Now we have a complex universe. It is still a) non-linear and b) dynamic, and it retains a lot of the features of the chaotic universe. However, this time there is feedback into the system from the emerging results. So in terms of economies, the individuals and groups’ buying and selling will result in an economy. The state of that economy then constrains and affects how those individuals and group can act.

As a diagram it might look like this:

A framework to help map where you are

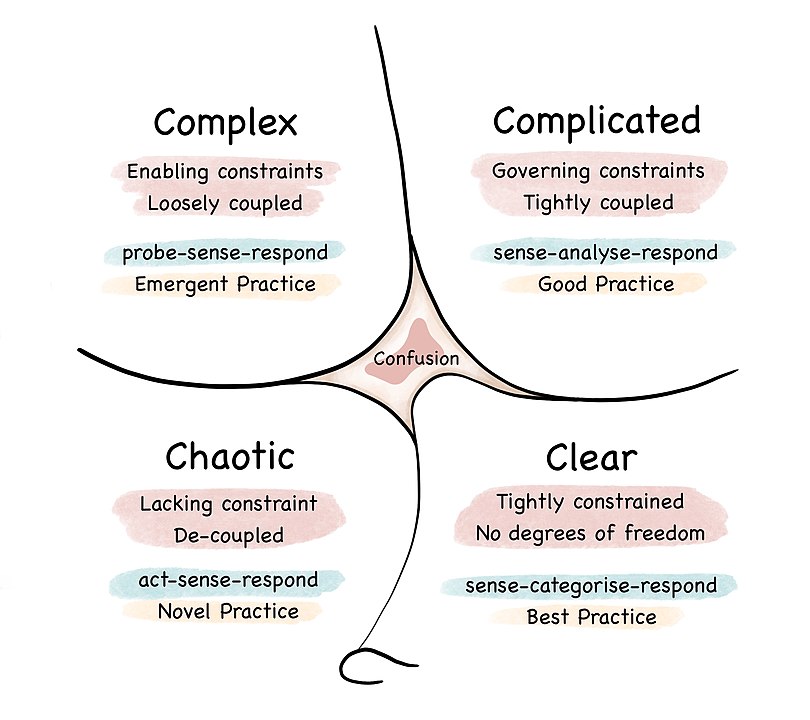

Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework digs into this in more depth. On the right you have the clockwork world view, and on the left the chaotic and the complex.

I’ll come back to it but it is worth pointing out the state of confusion at the centre of the diagram. This happens at the start of a project when you don’t know what the operating environment is.

Ordered (“Clockwork”) Systems

As a whole, ordered systems are linear. We could think of them as mechanical or clockwork systems in that results are predictable.

These ordered systems themselves fall into two broad categories, the simple and the complicated. Following the mechanical analogy, we can consider light switches and mixing desks. The light switch is a simple, ordered system: it is clear to all who use them what the effect is. A mixing desk, though, is a complicated, ordered system: we may know what effects it can have but it needs an expert hand to guide it.

Disordered (“Chaotic” and “Complex”) Systems

While ordered systems are predictable, even if only by an expert, disordered systems are not. Not only that, the actions of the elements within the system can fundamentally change it. Both chaotic and complex systems are where the butterflies roam.

Or for a more “homely”, example there is the pinball machine.

the ball’s movements are precisely governed by laws of gravitational rolling and elastic collisions—both fully understood—yet the final outcome is unpredictable.

Encyclopedia Britannica

So whichever disordered system we work in, chaotic and complex, we cannot ever be sure what impact our actions will have. This is a clear difficulty for those responsible for leading, but it gets worse. A second shared feature of both chaotic and complex systems is that their interwovenness means we cannot roll the system back. We cannot put Humpty Dumpty back together again. And a third is that our actions in these systems change the space we’re operating in.

While unpredictability and irreversibility are their common features, chaotic and complex systems differ in terms of what Snowden calls constraints. A chaotic system has no constraints, where a complex system does have them.

One example of constraints turning a potentially chaotic environment into a complex one is the film The Dirty Dozen. Set at the end of the Second World War, Lee Marvin’s character, Major Reisman, is tasked with shaping a group of 12 of the USA’s deadliest convicts into a working commando force. Given that he is working with murderers and worse, the potential for unpredictable behaviour is high, and almost guaranteed unless constraints are put in. Much of the start of the film revolves around the ex-inmates testing the boundaries. Reisman tells them the constraints.

For those of you who forgot, my name is Reisman. You have all volunteered for a mission that gives you three ways to go. You can foul up during training, you can foul up in action, in which case I will blow your brains out, or you can do as you’re told. In which case you may just get by. This is your new home. Do not try to escape. There will be no excuse, no appeal. Any attempt by one of you and you will all be sent directly back to prison for execution of sentence. You are therefore dependent upon each other. Any one of you try anything smart, and you all get it right in the neck. Am I clear?

Major Reisman, The Dirty Dozen (1967)

By doing so, Reisman is turning a chaotic set-up into a complex one. He is also foreshadowing some modern US military advice.

So if chaos is complexity without constraints, what is complexity? There are various academic definitions, such as this from Professor Paul Cilliers [via Sonja Blignaut]. Complex systems can be recognized as having 7 defining characteristics.

- Complex systems consist of a large number of elements that in themselves can be simple.

- The elements interact dynamically and in a non-linear fashion

- There are many direct and indirect feedback loops.

- Complex systems are open systems.

- Complex systems have memory distributed throughout the system. Any complex system thus has a history, and that history is of cardinal importance to the behaviour of the system.

- Since the interactions are rich, dynamic, fed back, and, above all, nonlinear, the behaviour of the system as a whole cannot be predicted from an inspection of its components. The notion of “emergence” is used to describe this aspect.

- Complex systems are adaptive. They can (re)organize their internal structure without the intervention of an external agent.

Less academically, and perhaps more practically, General Stanley McChrystal suggests timescale as a useful frame with which to try and diagnose complexity

Pit Stop: Types of environment and their characteristics

So to take stock, so far there are:

- Ordered systems – these are linear and predictable.

- Some are simple and clear. You don’t need an expert.

- Some are complicated. You will likely need an expert to help.

- The overriding metaphor here is machines.

- Disordered systems – these have multiple elements, are non-linear, not predictable and irreversible

- Some are chaotic. You have no way of knowing what will happen.

- Some are complex. These are chaotic systems with constraints put in to help.

- The overriding metaphor is biological.

With the exception of Cynefin and some of the military examples, a lot of that is what Aristotle might have called theoria. It gives us a useful, theoretical appreciation but it doesn’t any praxis, any context for why it might matter or what can go wrong when we do make a wrong assessment of the operating environment. Nor does it give us any clues to why we might all be so prone to misdiagnosis.

Misdiagnosis – The Janitor’s Tale

In The Power of Not Thinking, Simon Roberts tells has a wonderful “Parable of the Janitor” that brings some of these definitions to life.

To put it far more blandly, mistaking the environment and underestimating both the idiosyncracies in it and the number of complexities of the interactions within it leads to what you might euphemistically call “underperformance”.

Friedrich Hayek warned that this sort of misdiagnosis could lead to broader ranging harm.

But if there are such avoidable mistakes, why is it so easy for us to misdiagnose things and as Kinni says, default to complicate?

5 possible reasons for misdiagnosis

Snowden suggests that part of the reason might our own bias. If you go back the centre of that Cynefin framework, the confused bit where you haven’t yet diagnosed your operating environment, Snowden says we are most likely to assess the environment in terms of our own preferences. Bureaucrats tend to see ordered, process driven environments; politicians tend to see complex, “get everyone in a room” environments.

Part of the reason for our misdiagnosis might simply be the wrong tools. We might be recognising the complexity in the room, but using tools better suited for complicated environments. Muller remarks that

But these tools are not fit for the environment. They are ponderously slow, but perhaps more seriously assume that the same approaches that work in an ordered system apply in a disordered one.

A third reason for the default to complicated – or what is perceived as one – might just be old habits or that the approaches demanded by a complex environment are counterintuitive, even to some of the most decorated and successful leaders.

Or as Atul Gawande puts it, there is a seemingly contradictory mix at the heart of a complex system.

Fourth and potentially linked is energy. As McChrystal notes below, accepting that Iraq was a complex, rather than a complicated, domain, meant they had to overhaul the structures of JSOC. Not only that, doing so sacrificed some of the lean, mean fighting machine ethos for something messier and more organic.

Ego might play a part too.

It takes a confident leader to genuinely accept that they can’t understand every facet of the environment they are operating in and to genuinely seek out differing, perhaps opposing viewpoints.

Finally, managers may just prefer the sort of complicatedness that comes with a misdiagnosis. Snowden posted an interesting provocation on Mastodon

In a similar vein, Richard Koch suggests that the types of people who become managers, or who are responsible for assessing the lay of the land, often thrive on the sorts of problems complicatedness mentioned above. It’s easy to start armchair psychoanalysing but it’s not too much of a stretch to see think that the set of managerial skills many organisations promote will enjoy the results of a misdiagnosis.

Koch certainly thinks this default to complicatedness is endemic,

That all hopefully goes some way to helping to understand the types of environment we might operate in so that we can diagnose them accurately. The next step is to pick out the advice from all the authors on what do once you’ve made the correct diagnosis.

Next: 4 component parts: goals, structure, measurement and management.