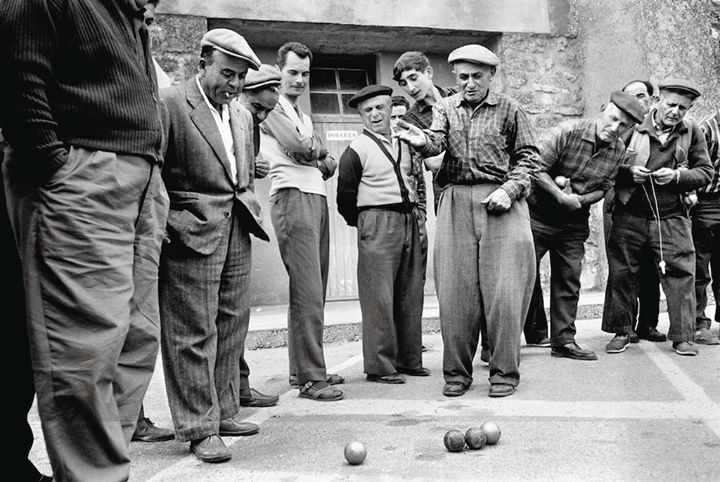

Heft might be due a revival. It’s a term that’s easier to understand than to define. It’s that feeling of a petanque ball in your hand – a solid weight, a thing with gravitas. The ideal heft weight, I am told, is between 600g and 800g. This physical sense of weight finds an unlikely echo in the Yorkshire Moors, where sheep are “hefted” to the landscape. Establishing a heft takes time and patience; shepherds must constantly guide their flocks until the animals learn their place. Each generation inherits this knowledge from their mothers, creating an unbroken chain of belonging. Heft, then, is both weight and rootedness – a slow-earned sense of significance and place.

This earned weight stands in stark contrast to our digital age’s cultivated lightness. We live in a world of infinite scrolls and swipes, of transient interactions optimised for convenience and speed. Our digital interfaces are deliberately frictionless, Vegas-like experiences designed to float us through without resistance. The technology that promises connection often delivers only its simulation – smooth, efficient, but somehow weightless and hollow. Yet this very smoothness brings whispered concerns: is technology, rather than helping, separating us from our better selves?

It is argued that the consequences of this lightness are perhaps most visible in our younger generations. Mental health, or the lack of it, is a worrying trend. As the British Medical Association reports: between 2017 and 2022, rates of probable mental disorder increased from one in eight young people aged 7-16 to more than one in six. For those aged 17-19, the increase was even more dramatic – from one in ten to one in four. While it would be too neat to draw direct lines between digital weightlessness and these challenges, thinkers like Jonathan Haidt point to deeper issues: the ubiquity of smartphones, the erasure of childhood risk, the fraying of community ties.

But perhaps Viktor Frankl would offer a different lens – one more aligned with heft. The challenge facing young people might not be merely technological but existential: a lack of meaning, responsibility, and connection to something larger than themselves. Frankl might argue that we focus too much on what is done to young people, and not enough on what young people can do for themselves. The current bleak outlook, he might suggest, stems not from a surfeit of smartphones but from a deficit of purpose.

A Frankl-style analysis certainly feels both less panicked and more respectful of the young. We see glimpses of this hunger for “heft” in unexpected places. When floods recently devastated Valencia, young Spanish volunteers – armed with both shovels and smartphones – demonstrated that technology need not preclude purpose. They showed that given the chance to contribute to something meaningful, to shoulder real responsibility, young people will grasp it with both hands.

This yearning for significance isn’t new. In 1968, a year that eerily mirrors our own time’s apparent chaos, two moments seem relevant. Martin Luther King Jr., in his “Remaining Awake” speech, challenged his audience to look beyond mere technological achievement:

“One day we will have to stand before the God of history and we will talk in terms of things we’ve done. Yes, we will be able to say we built gargantuan bridges to span the seas, we built gigantic buildings to kiss the skies. Yes, we made our submarines to penetrate oceanic depths. We brought into being many other things with our scientific and technological power.

It seems that I can hear the God of history saying, “That was not enough!“”

Later that same year, Robert F. Kennedy, announcing Martin Luther King’s assassination in Indianapolis, reached for Aeschylus to give weight to the moment:

“Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

In times of crisis, then, such cultural touchstones provided an anchor, tethering people to shared visions and stories of society. Today’s public figures rarely seem to carry such heft.

The challenge becomes particularly apparent in education, where we seem to have increasingly treated knowledge as content to be delivered rather than weight to be earned. For a while now, there has been a push in the UK and elsewhere to make teaching more of a science. It’s a noble idea, and you can see it the push to blend educational research, theory, and cognitive science from, to take just a few, ResearchEd, Cognitive Load Theory, or the EEF, or Daniel Willingham‘s Why Don’t Children Like School. We optimise for efficiency, breaking learning into digestible chunks, measuring progress in quantifiable metrics. In fairness, the model means we have become very good at learning things. This “knowledge as content” model is grist to the technologists’ mills, too.

It is, however, only a model and, problematically, one that enters us into a questionably linear world of flight paths and the tyranny of metrics. It make other debatable assumptions too: that learning is purely cognitive rather than embodied, that knowledge is static rather than social, that technology is a neutral tool rather than a force that shapes how we think and learn.

The results of this approach are visible in the story of John Stuart Mill. His father drilled him in classical texts from age three – by twelve, he had mastered Greek and Latin, physics and mathematics. Yet despite this impressive accumulation of knowledge, Mill suffered a breakdown. His cure, surprisingly, came through Wordsworth’s poetry

“What made Wordsworth’s poems a medicine for my state of mind, was that they expressed, not mere outward beauty, but states of feeling, and of thought coloured by feeling, under the excitement of beauty. They seemed to be the very culture of the feelings, which I was in quest of. In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy, of sympathetic and imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings“

As last 3 words would suggest, for Mill, the poems had heft.

This points to a deeper truth about education. The traditional Trivium recognises that facts alone are not enough – they must be wrapped in debate, social refinement, and creativity. Simon Robert’s wonderful “The Power of Not Thinking” reminds us that knowledge lives not just in our brains but in our bodies, our actions, our feelings. Perhaps true learning, like those hefted sheep, requires both freedom and constraint, both individual exploration and inherited wisdom.

And so perhaps this is our challenge: not just to critique the lightness of our age, or the frippery of Fortnite, but to intentionally restore heft to our lives and institutions. In education, this might mean protecting spaces for messy, meaningful learning alongside efficient content delivery. In technology, it could mean designing for resistance as well as smoothness – creating digital experiences that encourage depth rather than just ease. And in our communities, it might mean more urgency creating opportunities for young people to shoulder real responsibility, to connect with something larger than themselves.

We might find, in the end, that like those hefted sheep in the Lake District, what we need isn’t freedom from all constraints, but the right kind of rootedness – a sense of place and purpose earned through time and effort, passed down through generations, anchoring us in an increasingly weightless world. The path forward requires more than just reaction to the lightness of technology; it requires the intentional protection and promotion of those weightier parts of life that tether us to meaning, responsibility, and connection.

Notes & thanks

This is my attempt to structure some of my thinking following a fascinating discussion last Wednesday with Michael Foley, Rob Poynton and others. It was Michael’s small, but definitely hefty, book Life Lessons from Bergson that provided an impetus for the gathering, and his wonderful musings on heft as “a thing” between 600g and 800g that prompted both a comment from Janeena Sims about sheep and a discussion amongst many people much wiser than me all of which is 90% of the above